A Practical Guide to eBPF Licensing: Or How I Learned to Stop Worrying and Love the GPL

Disclaimer: We are not lawyers and this is not legal advice. Please contact a lawyer for legal advice.

Authors: Bill Mulligan and Liz Rice

While there is a wide appreciation of the power of eBPF to fundamentally change the platforms we run our software on, there are some misconceptions in the ecosystem about when eBPF programs need to be licensed under the GPL and how that impacts licensing compliance. Seeing GPL licensed code may give some legal teams pause because eBPF is unfamiliar to them - but it shouldn’t. This blog provides context around why GPL licensed eBPF code exists and lays out why if you are already using Linux in your project, product, or company then using eBPF should not cause any additional concerns. If you are a contributor to a project already using eBPF or looking to add it, or you're unfamiliar with or concerned about eBPF licensing, this blog will walk you through some practical strategies for eBPF licensing and hopefully you’ll learn to stop worrying and love the GPL.

Note: this article considers situations where eBPF programs are executed within the Linux kernel, which is the case for the majority of deployed eBPF applications today. It's also possible to run eBPF bytecode in other ways, for example in a userspace eBPF runtime, where different licensing models can apply.

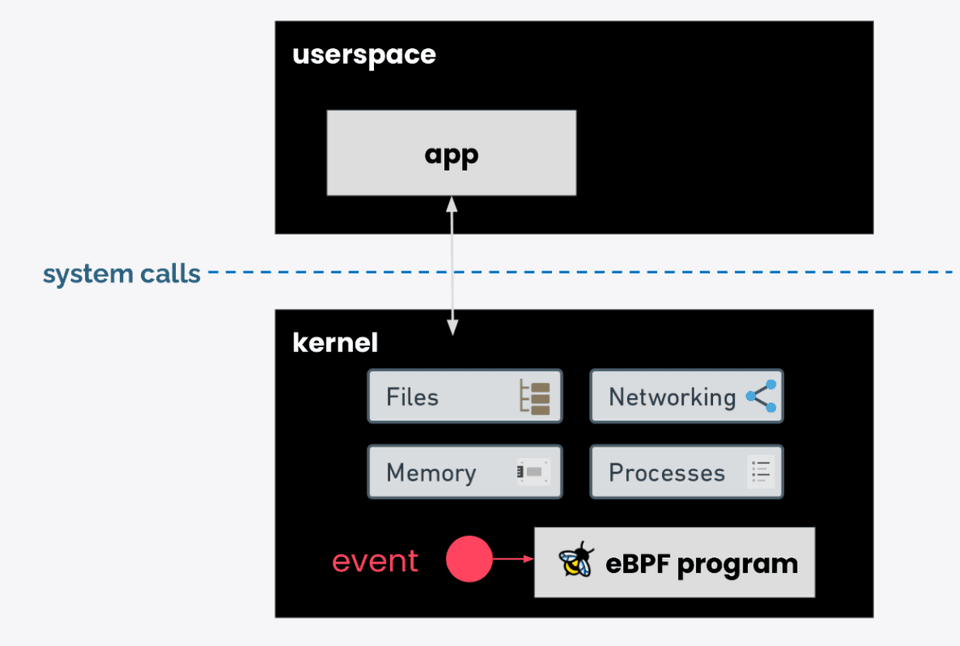

Most eBPF-based projects consist of user space code, plus eBPF programs that run in the kernel. Much like kernel modules, eBPF programs have the ability to significantly extend or change kernel behaviors. eBPF programs are dynamically linked with the kernel when they’re loaded into it using the bpf() system call.

When an eBPF program is loaded into the Linux kernel, the kernel checks which functions it intends to use. If any function is marked as “GPL only,” the eBPF program has to have a GPL-compatible license from the licensing scheme documented here. The kernel rejects the eBPF program if it does not have a compatible license. The code for establishing this compatibility (license_is_gpl_compatible()) is defined here.

Not all eBPF helper functions are marked as “GPL only”, so it is theoretically possible for some eBPF programs not to need GPL-compatible licensing. However, Alexei Staravoitov, co-maintainer of eBPF in the kernel, has stated that "all meaningful eBPF programs are GPL" because key helper functions are GPL-ed. Furthermore, some eBPF program types are required to be GPL compatible even if they don’t use “GPL only” helper functions directly, because they implicitly call EXPORT_SYMBOL_GPL kernel functions and any new eBPF programs backed by kfuncs will also need to be GPL licensed. Therefore, it is highly impractical to avoid licensing eBPF bytecode as GPL.

Most projects use a dual license of GPLv2 and a permissive Open Source license such as MIT, BSD-2-Clause, or Apache-2.0. eBPF programs use a line of code such as char _license[] SEC("license") = "Dual BSD/GPL" to convey the license string to the kernel. However, this license string is not a substitute for the SPDX identifier in the source file which you need to provide for license auditing purposes.

If an eBPF program needs to be GPL licensed, what does that mean for your userspace executables? Can a non-GPL'd user space executable bundle/load/interact with GPL licensed eBPF bytecode running inside the kernel? Yes! The intent is for this to be normal, reasonable practice. All of the userspace interactions fall under a Linux kernel syscall API exception. All applications running in user space interact with the kernel using the syscall interface, and the same is true for user space applications that interact with eBPF programs in the kernel.

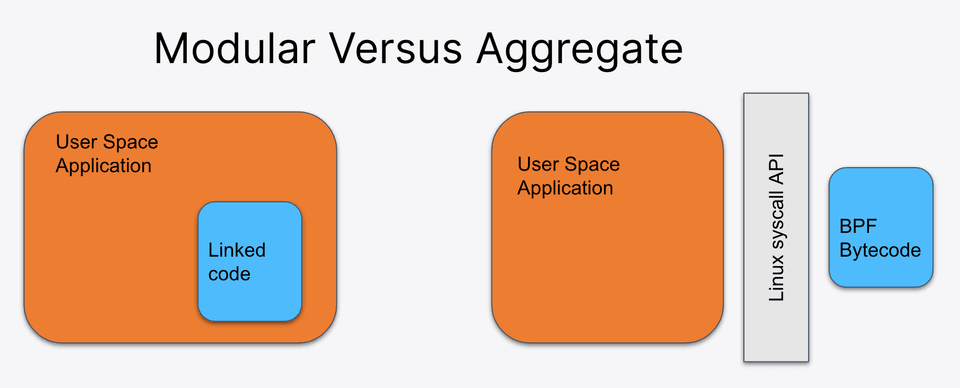

With the GPL derived works, external code that is either linked statically at build time or dynamically at runtime, and modular programs (single applications that may execute separately but depend on detailed communication of internal data structures or shared memory), must be distributed in a GPL compatible manner. However, userspace executables that load or interact with eBPF programs are none of the above.

The Linux kernel developers have made a very deliberate effort to provide documented intent around the issue of what compromises a derived work of the Linux kernel and what does not. They have designated the set of system calls as the syscall API that can be called from other programs without those programs being considered a derived work of the kernel.

A userspace executable and the related eBPF bytecode is generally considered an aggregate of the two pieces of software. They are two separate works that interact via the Linux syscall API to get useful work done and can be packaged together without being considered modular parts of a single application derived from the Linux kernel. Aggregates are a number of separate programs, distributed together that communicate with each other as if they were independent executables on the system (using standard OS provided mechanisms such as pipes or file descriptors). The GPLv2 FAQ lays out that the creation and that distribution of an aggregate, of GPL and non-GPL compatible code, should be permitted.

eBPF programs have no ability to link either statically or dynamically with user space code. User space applications interact with the in-kernel eBPF program exclusively through the syscall interface, in the same way they interact with any other aspect of the kernel, and thus are not derivative works. This is expressly described in the Linux syscall note and further clarified in the eBPF licensing section “Generally, proprietary-licensed applications and GPL licensed BPF programs written for the Linux kernel in the same package can co-exist because they are separate executable processes.”

While eBPF licensing may seem complex, understanding GPL compatibility and the distinction between kernel space and user space components clarifies compliance strategies. The delineation between eBPF bytecode in the kernel and userspace executables helps mitigate concerns about GPL compatibility, affirming the flexibility of picking a license for userspace applications. Ultimately, with more clarity on licensing and a shared understanding of best practices, the eBPF ecosystem can continue to evolve and drive the silent platform revolution.

If you want to learn more about this topic, please also check the KubeCon + CloudNativeCon talk and for other runtimes check out the kernel documentation.

Share on social media:

Subscribe to bi-weekly eCHO News

Keep up on the latest news and information from the eBPF and Cilium